“On the day that Berry Gordy started Motown, there were five of us there. He sat us down and said, ‘We are not going to make Black music. We’re going to make music for people. We’re going to make music for the world.'”

(Robinson, Smokey; “10 Questions: Smokey Robinson Will Now Take Your Questions”; Time; 2/2/2009.)

With that aim, Gordy built one of the largest black entertainment conglomerates in American business history. No. He built one of the largest entertainment conglomerates in American history.

Berry Gordy is reminiscent of other American pioneering entrepreneurs who built their business and their success from just a few dollars, a few good ideas, and a lot of ambition. Think Henry Ford, a predecessor. Think Ray Kroc (McDonald’s), a contemporary. Both of these men took a known innovation in business and manufacturing — the division of labor, born a century or so before their times — and adapted it to their product. (McCraw, 2000.)

In 1959 Berry Gordy took that principle and adapted it to his product: music performers, records, and the songs that make them possible. He did it without the support of large financial backers or a surrounding music business hub of activity.

Like many successful entrepreneurs, Gordy created a product people did not know they wanted or needed until he presented it to them. Sure, some might say he was lucky by being in the right place and the right time. But many other aspiring black songwriter-musician-businesspersons were in that same right place and time. It was Gordy who was prepared: he had the vision, the ability to learn the business, the organizational skills, the songwriting skills, and an intense desire to avoid returning to work at the Detroit Lincoln Mercury plant.

Cultural Forces Align

His preparedness met opportunity, as the saying goes. Motown Records was wildly successful due to a combination of social-historical factors in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Among these were the northern migration of African-Americans after World War II and the painful birthing of the racial equality movement (triggered by Harry Truman’s 1948 executive order to integrate the armed forces). (McCraw, 2000.)

Concurrently, there was an explosion brewing of a form of black-produced, -performed, and -marketed popular music that would crossover to the (Caucasian) masses of the record-buying public. Berry Gordy’s genius was in merging these social-historical effects with the manufacturing business efficiency of assembly line production. In an ultimate best-of-both-worlds scenario, Motown Records created great music and great business. It established an iconic entertainment entity, a music genre, and a brand that became recognized worldwide; and it created a lot of wealth for many people. One plus one made three.

Without turning this story into a play-by-play biographical resume, there are some important events in Gordy’s early life that would affect his business future. His parents were from Georgia, with roots in farming. In 1922 they packed up the family and moved, not to Bev-er-ly, but to Detroit, Michigan, probably with an eye on an auto plant job for Berry’s father.

Word had spread about Henry Ford, his assembly line, and his generous five-dollar-a-day pay rate. And that other auto industry genius Alfred Sloan had taken the reins of General Motors by then. Both companies were in serious pursuit of market share, and they had been hiring tens of thousands of new employees over the previous 10 years. Despite the depression of 1920-21, Ford Motor Company had just broken ground on an enormous new manufacturing complex. (McCraw, 2000.)

In the mid-1950s, Berry went to work at the (Ford) Lincoln Mercury plant in Detroit. He experienced firsthand the miracle of the assembly line. It produced good pay and affordable cars for workers, but the work was hard and tedious. Ultimately, Gordy had more creative aspirations on his mind, and in 1957 he quit the plant to pursue his dream of becoming a professional songwriter. He had learned how the assembly line supercharged the division of labor concept. Now he was preparing to adapt this same idea to the business of music. (“Berry Gordy’s Motown,” n.d.)

In the late 1950s, many African-Americans enjoyed rhythm and blues music, but it was routinely unprofitable and often performed in shabby venues. Berry Gordy, who would become one of the greatest entrepreneurs in history, would change that. He had a vision of taking black-inspired music out of the slums and giving it broad, national appeal as a respectable art form. (Folsom, 1998.)

Family Business

In 1959, with the urging of his friend Smokey Robinson, Gordy borrowed $800 from his family to begin building his empire. He made a decision to keep it in Detroit rather than move to a music business hub like New York or Chicago. Gordy started his company with the most primitive of recording equipment and facilities and a bare-bones staff of mostly family. (White & Barnes, 1994.)

His father did the plastering and repairs, and his sister did the bookkeeping. The vocal studio was in the hallway, and his echo chamber was the downstairs bathroom. “We had to post a guard outside the door,” Gordy says, “to make sure no one flushed the toilet while we were recording.” (Folsom, 1998.)

Those were the halcyon days of Motown’s infancy. Like a young married couple just starting out in life, they did not have material abundance, but they were hopeful and confident. The entire staff had a sense of good things to come. Besides, they were still young and idealistic enough to love creating music for music’s sake.

The fledgling record company soon began to experience a small amount of success, and the artist and songwriter stables started growing and maturing. It was in those early days that Gordy gradually developed his assembly line method of production. By the latter part of the twentieth century, the term artist development had become a well-known concept among record companies, with vice presidents of artist development to oversee entire divisions. In the early 1960s, however, it was still an experimental concept, albeit, a concept that made sense once it was considered — much like the auto production line. Berry’s sisters Gwen and Anna convinced him to let them develop their “kick, turn, and smile” version of artist charm school. With its subsequent success, the charm school (not their term, to be sure) became an integral station on Motown’s artist production line.

The Music

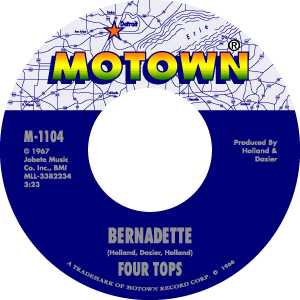

The process soon became unstoppable. Some say the Motown Records house ensemble of backing musicians (later known as the Funk Brothers) have played on more Number One hits than the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Elvis combined. Although this statistic has not been confirmed (except through an academically unacceptable website source), the point is clear. Motown produced literally hundreds of hit records, the business proof of which is in the company’s past worth: $40 million in 1973 and No. 1 on the Black Enterprise rankings of black-owned companies from 1973 to 1983. (Meeks, 2005.) The aesthetic proof is in the ubiquity of the 1960s and ‘70s hits. They are still the mainstay of many commercial radio stations and countless professional and garage bands.

Some might say the music was watered-down rhythm and blues and soul. But judged by its commercial and popular success, again, Motown achieved the best of both worlds: a crossover sound that incorporated a spectacular combination of authentic black music consciousness with palatability for the masses. Caucasians were hungering for an alternative to the white-bread selection of popular music offered them at the time.

Not to belabor the point, but the music as well as the business philosophy was good. As mentioned, an indispensable part of the Motown sound (and the production line) was the group of regular studio musicians later dubbed the Funk Brothers. The same basic crew of players performed on virtually all of Motown’s records until the company relocated to Los Angeles in 1972. They were mostly accomplished jazz musicians. But back then (like today), jazz did not always pay the bills. Though occasionally complaining about this pop music they had to play, and occasionally trying to make it more cerebral (which, to his credit, Gordy always shot down), the Funk Brothers became a legend in American music business history. (White & Barnes, 1994.)

The Production Line

The Motown production system had two primary elements: the performers and the songs. As stated, Motown had an efficient artist development department. Once they admitted talent into the fold, the grooming began. Female performers (mostly teenagers) were put through the Motown charm school to learn manners, taste and class (at least, Motown’s version of these), fashion, and onstage presence. A separate program existed for male performers. The company wanted to project a well-mannered, clean-cut image for its performers, on- and offstage. They believed in it, and apparently, it worked. The company had a fashion department to produce and select stage costumes as well as offstage apparel. There were dedicated makeup facilities. Additionally, Motown helped their young stars with the business side of their careers, including taxes, contracts, etc. (“Critical Brief History,” n.d.)

On the musical side of the business resided a well-tuned song production team. With few early exceptions (Smokey Robinson and Marvin Gaye are two), songwriters were a separate entity from performers at Motown, in keeping with the division of labor. Songwriting teams would produce their product each week. From there it went through a vetting process that Gordy designed to ensure that only the best songs made it to record. He established a committee system to choose an artist’s next song to record. After that, it often went back to the songwriter for additional touch-up, then on to the musical director who prepared it for recording. The director would distribute the sheet music, briefly rehearse the Funk Brothers and the name artist, schedule the recording studio and technicians, and record the song. It was like clockwork, and it occurred many times daily. (Dannen, 1991.)

This is the story of Motown’s rise: how the assembly line method of music production and artist development, social-historical factors (black northern migration, the infancy of the racial equality movement), and Gordy’s pop music intelligence all combined to put Motown into the pantheon of music corporations.

On a final note, there was also a social consciousness side to Berry Gordy and Motown Records. Many have credited him for bringing the races together through music. Additionally, he had a special artist and teacher in Marvin Gaye, though Gordy was the boss. Berry describes it:

“I did not like the idea that Marvin, who was so popular with the women, wanted to sing protest songs. He called me when I was on vacation in the Bahamas and told me what he wanted to do. I told him, ‘Marvin, why do you want to talk about police brutality, the Vietnam War? You’ve got this great, sexy image. Why blow it?'”

“‘I don’t care about no image, BG’, he told me. ‘I just want to awaken the minds of mankind.'”

“That was heavy. I loved it when he said that. ‘OK, Marvin,’ I told him, ‘if you’re wrong, you’ll learn something — and if you’re right, I’ll learn something.'”

“I learned something.” (White & Barnes, 1994.)■

BERRY GORDY JR. / MOTOWN TIMELINE

1922 – Berry Gordy Jr.’s parents relocate to Detroit, Mich., from Milledgeville, Ga., as part of the northern migration

1929 – Berry Gordy Jr., is born at Detroit’s Harper Hospital

1948 – Gordy drops out of high school in 11th grade to become a boxer

1949 – The Flame Show Bar opened in 1949, located at John R and Canfield, which was the showplace for top black talent in Detroit during the 1950s

1951 – Gordy is drafted into the military and shipped to Korea

1953 – Gordy returns home from Korea, marries Thelma Coleman, and opens the 3-D Record Mart — House of Jazz

1955 – Gordy’s record store goes bankrupt, largely due to his refusal to stock blues records because he was a jazz snob

1955 – Gordy starts work at the Lincoln-Mercury auto plant; he lasts about two years

1957 – Gordy is invited to write songs for Flame Show Bar owner’s artists, including singer Jackie Wilson; they begin a co-songwriting partnership

1957 – Gordy’s 1st songwriting success: “Reet Petite,” recorded by Jackie Wilson

1958 – Over the coming year, Jackie Wilson records six more songs co-written with Gordy, including “Lonely Teardrops”; Gordy feels that he didn’t earn as much as he deserved from these royalties and realizes the real money is in producing and publishing

1959 – Berry borrows $800 from his family, at Smokey Robinson’s urging, and buys a house at 2648 W. Grand Boulevard, Detroit, Mich., to found Motown Records (He originally formed two record labels, Tamla Records and Motown Records, to avoid accusations of payola should DJs play too many records from one label. These and other subsequent subsidiary labels all used the same musicians, songwriters, and staff, and were all under the umbrella of the Motown Record Corporation, or commonly known as Motown.) Barry eventually names his new headquarters Hitsville U.S.A.

1959 – Tamla Records 1st release: Marv Johnson’s “Come to Me”

1959 – Tamla Records 1st hit: Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want)”

1959 – Gordy’s 1st signed act: The Matadors (subsequently renamed The Miracles); Gordy produces the 1st Miracles record “Got a Job,” which is picked up by New York label End Records

1960 – Motown and the Miracles release their 1st Number 1 R&B hit: “Shop Around”

1960 – Motown Record Corporation is formally incorporated

1961 – Motown and The Marvelettes release their 1st U.S. Number 1 pop hit: “Please Mr. Postman”

1966 – Motown now occupies seven neighboring houses in addition to the original Hitsville U.S.A. house

1961 – Motown produces 110 Top 10 hits over the next 10 years

1967 – Holland–Dozier–Holland leave Motown over royalty payment disputes; Norman Whitfield becomes Motown’s top producer

1969 – Motown begins gradually moving its operations to Los Angeles; Berry wants to begin expanding into the movie business

1970 – Motown begins allowing artists to write and produce more of their own material

1971 – Motown and Marvin Gaye release album What’s Going On

1972 – Gordy consolidates all Motown operations to Los Angeles, Calif.

1972 – Motown and Stevie Wonder release album Music of My Mind

1972 – Motown and Stevie Wonder release album Talking Book

1973 – Motown and Stevie Wonder release album Innervision

1973 – Motown and Marvin Gaye release album Let’s Get It On

1975 – Motown continues to produce successful artists such as Lionel Richie and the Commodores, Rick James, Teena Marie, the Dazz Band, DeBarge

1985 – Motown begins losing money

1988 – Gordy sells Motown to MCA and Boston Ventures for $61 million; the company is subsequently bought and sold several times

2011 – Motown is reactivated under The Island Def Jam Music Group division of Universal Music Group, and is currently based in New York City

References:

“Berry Gordy’s Motown Records”; History-of-rock.com; n.d.

“Critical Brief History of Motown Records”; FortuneCity.com; n.d.

Dannen, Fredric; Hit Men: Power Brokers and Fast Money Inside the Music Business; 1991.

Folsom, Burton W.; “Berry Gordy and Motown Records: Lessons for Black History Month”; Mackinac.org; 2/2/1998.

Meeks, Kenneth; “Berry Gordy: America’s First Black Music Mogul”; Black Enterprise; October 2005.

McCraw, Thomas K.; American Business, 1920-2000: How It Worked; 2000.

White, Adam; “Gordy Speaks”; Billboard; 11/5/1994.

Leave a Reply